The Scientist in the Crib

My name is

Dov Katz. My training is in roboticis. My research and work are focused on the intersection of computer vision, machine learning and robotics. I also enjoy writing about these topics.

Here are some thoughts about Interactive Perception as I originally published on

Medium:

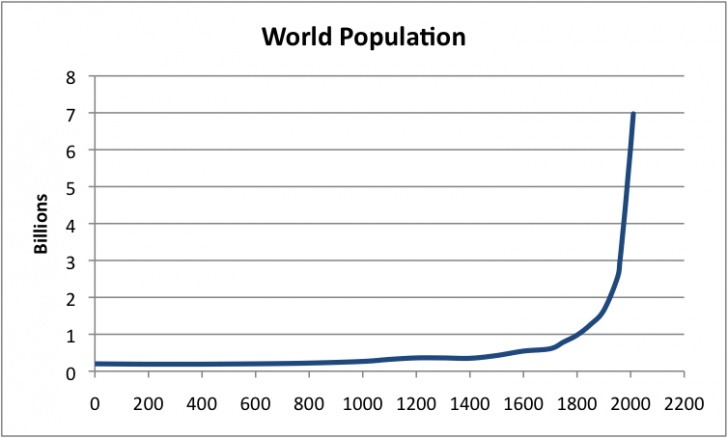

Human Learning

Humanity’s advantage over the rest of the biosphere is out amazing abaility to learn and adapt. Alison Gopnik, Andrew N. Meltzoff and Patricia K. Kuhl. wrote a book called “The Scientist in the Crib” that discusses how babies learn.

Scientific Learning

Scientists often start with a crude, intuitive understanding of a phenomena. They then explore it by conducting some experiments. But, to conduct insightful experiments, scientists spend considerable amount of time learning what others have done. Typically, a scientific experiment is the last floor in a very tall building, sometimes extending decades or even centuries back.

Children Learning

So how do children learn? They begin with some crude knowledge provided by our genes. For instance, researchers have demonstrated that newborns already understand the concept of momentum. If you show a newborn a moving object that disappears behind a blanket, they expected it to reappear on the other based on its velocity and direction.

Of course, there’s only so much knowledge that can be hardcoded. Most things have to be learnt. Children appear to be spending much time playing. But, really, they are conducting serious experiments. What happens when I paint the wall? Will the glass break if I drop it? Is twisting the doorknob the right way to move the door?

Finally, there are teacher, also known as “parents”. The world is pretty complex. Making sense of it by running experiments alone isn’t practical. A parent, however, can give us a shove in the right direction to maximize our learning. This is what researchers refer to as “structure”. When you have a sense of how to organize things, discovery the logic behind a phenomena becomes easier.

The "Scientist in the Crib" book

The “Scientist in the Crib” does a good job describing these three components of learning: what we’re born with, what we learn from experimenting, and the role of teachers. It includes some fascinating examples demonstrating we are born with quite a bit of knowledge.

An interesting topic in the book is the brain’s plasticity. This is the notion that our brain is extremely adaptive. For instance, Japanese and English speakers are sensitive to different sounds. An adult speaker might not be able to hear a certain sound because of their cultural background. Babies, however, are able to hear all sounds regardless of their culture. This demonstrates brain plasticity — because culturally we don’t need to distinguish between two sounds, the adult brain adapts and can no more hear the unnecessary sound,

If you find this topic interesting, I highly recommend reading the book!